Basic Information

PFAS are man-made, manufactured chemicals that are used in many industries around the world for a variety of consumer products (non-stick cookware, Teflon, dental floss, water-resistant clothing, paints, and many other commercial household products). Some of the more common PFAS chemicals include PFOA (Perfluorooctanoic Acid), PFOS (Perfluorooctane Sulfonate), and GenX. PFOA and PFOS have been studied and manufactured the most in comparison to the rest of PFAS. These two chemicals can be found in the environment and within the human body because they do not break down but instead accumulate, resulting in adverse health effects on people (cancer, low infant birth weights, thyroid hormone disruption, increased cholesterol levels and overall negative effects on the immune system). The other common or well-known PFAS chemical, GenX, is used to make high-performance fluoropolymers (non-stick coatings) and is often found in surface and groundwater, drinking water, rainwater, and in air emissions. The EPA states that PFOS and PFOA are no longer being used in today’s industry as they have been “voluntarily phased out,” whereas GenX is still widely used in today’s economy.

Exposure

Though PFOA and PFOS have been phased out of the industry, these chemicals do not break down over time and are still found in the environment. With PFAS being used in food packaging and production facilities, the chemical can easily enter the human body if it hasn’t already through drinking water or through other consumption methods where PFAS is commonly found. According to David Andrews, Senior Scientist from EWG, it is estimated that more than 1,500 drinking water systems in the United States are contaminated with these chemicals, while additional tests show that 28% of water utilities around the nation contained PFAS chemicals at concentrations at or above 5 ppt. When the analysis was bumped down to 2.5 ppt, the percentage of samples that displayed PFAS contamination doubled, suggesting that up to 110 million Americans could have PFAS in their water.

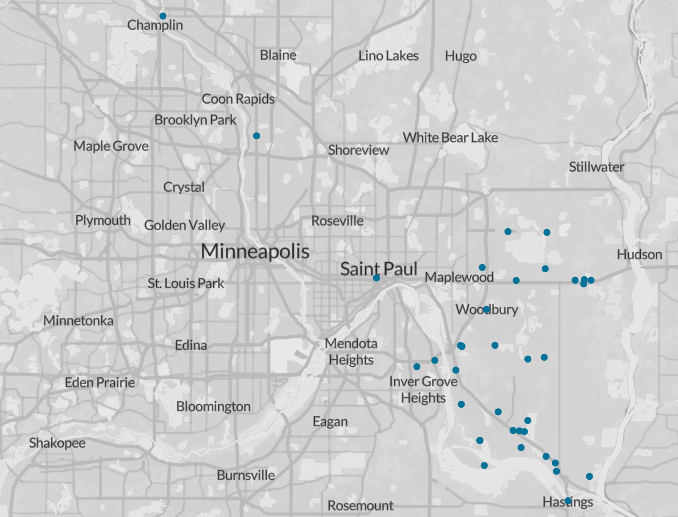

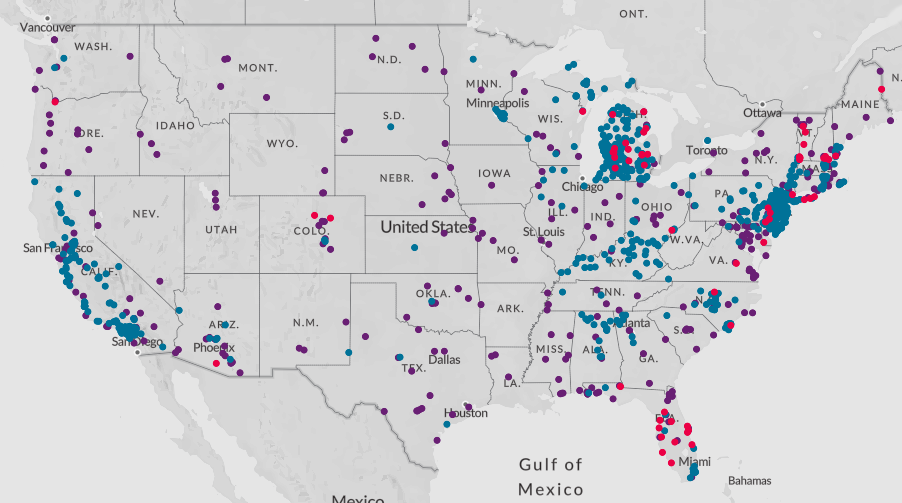

More recently, EWG decided to conduct an additional study between May and December of 2019. In this study, they tested 44 areas around the United States and found only one location to not contain PFAS chemicals. There were 34 areas where EWG received water samples containing PFAS that the EPA had not reported publicly. Since PFAS was not being regulated, facilities or utility companies that tested independently did not have to report to the EPA or go public with their results. Below, Figure 1 displays the locations that PFAS was found in drinking water in the local Twin Cities area, and Figure 2 displays PFAS contamination locations for the entirety of the United States. Both images were gathered from EWG’s PFAS study and are current as of March 2020.

EPA TRI Regulation Information

With the recent and concerning information regarding PFAS and their adverse health effects, as well as their growing accumulation in the environment, the NDAA has added PFAS chemicals to the EPCRA Section 313 list of reportable toxic chemicals as of January 1, 2020. The NDAA identified 14 PFAS chemicals by name and/or CASRN (Chemical Abstract Service Registry Number) and recognized additional PFAS based on additional criteria.

The first criteria point is that the PFAS chemical must be listed as an active chemical in the TSCA Inventory Section 8 (b). Section 8 (b) of TSCA is a record or list of chemicals that are manufactured or processed in the United States. Manufacturing is defined as “the facility [producing] the chemical for distribution or to be used for another on-site process.” Processing is defined as “distributing a chemical into commerce either as a reactant in the manufacturing of another substance or through the chemical being added as a formulation component to a product which is then distributed into commerce.”

If the chemical is listed on the TSCA list of chemicals and the chemical was found listed in the four tables found in section 721.9582 of Title 40, then the chemical is counted as reportable by the NDAA. For example, if the chemical is included on the TSCA list of chemicals and the chemical is manufactured or processed for use as part of carpets or to treat carpets, then it would also be considered reportable. A carpet is defined as “a finished fabric or similar product intended to be used as a floor covering. This definition excludes resilient floor coverings such as linoleum and vinyl tile.” Details, including exemptions for chemicals found in the tables of Section 721.9582 and information on whether or not a chemical is manufactured or processed for use relating to carpets in Section 721.10536, are listed in the Title 40 PDF linked above.

With the considerations described above, 170 PFAS chemicals were identified. Furthermore, the NDAA specified 14 additional PFAS to add to the TRI list. Twelve of these 14 chemicals were among the 170 chemicals described above. With the addition of the other two, there are a total of 172 PFAS chemicals subject to the NDAA.

The NDAA requires that PFAS subject to a claim of protection from disclosure must be reviewed by an administrator. The administrator must review any claim of protection from disclosure and must reassert and substantiate that claim in accordance with Section 14(f) of the Toxic Substances Control Act. If the administrator determines that the chemical identity of a PFAS substance qualifies for protection from disclosure, the administrator will include the substance on the Toxics Release Inventory in a way that does not disclose any protected information.

Until the EPA completes this process, PFAS chemicals that are subject to a claim of protection will not be added to the EPCRA Section 313 toxic chemical list. As mentioned previously, when PFAS were not regulated, utilities were not reporting to the EPA and not sharing their PFAS test results and data. Now, with the addition of PFAS to the TRI list of chemicals, it is no longer acceptable to not disclose PFAS information and any data collected from an independent study. Facilities are now required to report and make the data available and accessible to the public.

Reports for PFAS chemicals will be due to the EPA by July 1, 2021, for reporting year 2020 data; this further requires that TRI-covered industry sector facilities start collecting and tracking PFAS chemical data during 2020. To track the use of PFAS chemicals, the use of GHS-compliant Safety Data Sheets will be paramount. Chemical manufacturing facilities are now regulated to supply SDSs that have all sections and information required by the new GHS regulation. The complete list of regulated PFAS chemicals can be found on the EPA’s website. PFAS chemicals will have a 100-pound reporting threshold for all manufacturing, processing and otherwise use of the chemical. Regarding TRI reporting requirements, all requirements also apply to PFAS, including TRI exemptions.

EPA Enforcement

If a facility does not report by July 1 or if they are found to be non-compliant, it is possible that the EPA may issue fines upwards of $57,317. The most recent non-compliant fine was in November of 2019 where a manufacturing facility in Connecticut was fined $75,000 for failing to file their 2019 TRI report. As we discuss the additions of PFAS chemicals to the 2021 TRI reports, it is imperative that we are reminded of the importance of facilities being correctly evaluated and that chemical usage and storage are not overlooked when it comes to assessing for TRI reporting.

Sources

“Basic Information on PFAS.” EPA, Environmental Protection Agency, 6 Dec. 2018, www.epa.gov/pfas/basic-information-pfas.

“The Devil We Know.” Get the Facts – The Devil We Know, thedevilweknow.com/get-the-facts/.

Evans, Sydney, et al. “PFAS Contamination of Drinking Water Far More Prevalent Than Previously Reported.” EWG, 22 Jan. 2020, www.ewg.org/research/national-pfas-testing/.

“Drinking Water Health Advisories for PFOA and PFOS.” EPA, Environmental Protection Agency, 13 Feb. 2019, www.epa.gov/ground-water-and-drinking-water/drinking-water-health-advisories-pfoa-and-pfos.

“Environmental Protection Agency Toxic Release Inventory Reporting Requirements.” EPA, Environmental Protection Agency, www3.epa.gov/enviro/triexplorer/triexplorertutorial/content/demo_transcript.htm#sectionIII.

“About the TSCA Chemical Substance Inventory.” EPA, Environmental Protection Agency, 24 Sept. 2019, www.epa.gov/tsca-inventory/about-tsca-chemical-substance-inventory.

“Enforcement Policy, Guidance & Publications.” EPA, Environmental Protection Agency, 20 Jan. 2020, www.epa.gov/enforcement/enforcement-policy-guidance-publications.

“EPA Settlement with Connecticut Electric Cable Facility Resolves Alleged Chemical Reporting Violations.” EPA, Environmental Protection Agency, 20 Nov. 2019, www.epa.gov/newsreleases/epa-settlement-connecticut-electric-cable-facility-resolves-alleged-chemical-reporting.